Edward Ray is a British composer, sound designer, and audio lead working across video games and virtual reality. His work spans orchestral scoring, modular synthesis, sound design, and beyond, with a focus on narrative-driven composition and system-level audio implementation.

Currently serving as Audio Design Lead on a major global title, Edward Ray specializes in creating emotionally precise music and tactile sound that integrates tightly with gameplay across console, mobile, and PC platforms. This article turns his experience into paramount questions every ambitious composer should ask to grow and level up their craft.

How do I start a track with intention, not just inspiration?

Edward Ray’s compositional process begins not with chords or melody, but with questions: What is the music expressing? What role does it play in the narrative? That emotional foundation guides every decision.

Instead of jamming until something clicks, Ray shapes the emotional contour before opening his digital audio workstation (DAW). Only then do harmony, pacing, texture, and structure fall into place.

“A track sounding ‘nice’ doesn’t mean it’s right. You need a clear understanding of purpose before writing a single note… That’s a hill I’m prepared to die on. Knowing when it’s finished is simpler. The moment you start polishing in circles, it’s been done for a while.”

His rule of thumb? If taking anything away weakens the track, it's finished. Unless, of course, the deadline arrives first.

Which DAW should I use?

While many composers bounce between DAWs, Ray has sculpted REAPER into a personal creative engine, running everything from orchestral scores to modular synth mayhem. He writes custom scripts to automate repetitive tasks and swears by FabFilter plugins, MetaPlugin chains, and hands-on hardware like pedals and modular synths.

“Any task that takes longer than a minute gets written down, and I’ll spend Friday scripting it, and it pays off immediately.”

Ray warps sample libraries until they’re unrecognizable, using Sonuscore, Spitfire, and Orchestral Tools as raw materials, not shortcuts.

What do most composers overlook early in their careers?

Edward Ray’s creative process begins with a simple but powerful habit: listening. And not just to music, but to people. As a composer, sound designer, and audio lead, he emphasizes the importance of tuning in to your collaborators just as carefully as you do to a score or a soundscape. Ray believes that most creative blocks come from a failure to truly understand the project’s emotional intent.

“You shouldn’t find yourself at 1:00 a.m. thinking, ‘I don’t know what to do.’ That usually means you weren’t paying attention.”

His workflow includes written reports that summarize what the music is meant to express, aligned with collaborators before writing begins.

How should I organize my samples for maximum creativity?

Ray doesn’t organize libraries by vendor or branding. He tags by function and emotional behavior: fractured, powdered, percussive wreckage...

“I firmly believe structure is not a luxury. It is a requirement. Disorder in the library often mirrors disorder in the timeline.”

He renames, retags, and classifies every asset so that the creative flow isn’t interrupted by aimless searching. When he finds a five-year-old recording exactly where he hoped, it affirms his entire approach.

How can I manage versions and feedback like a pro?

Ray monitors each iteration of a track with detailed notes. When feedback rolls in, he never overwrites the original session; he forks it.

“I maintain two versions: one untouched, one for presentation. The original concept is never sacrificed in the name of short-term fixes. And version control is a discipline. There is no excuse for ambiguity in a professional workflow.”

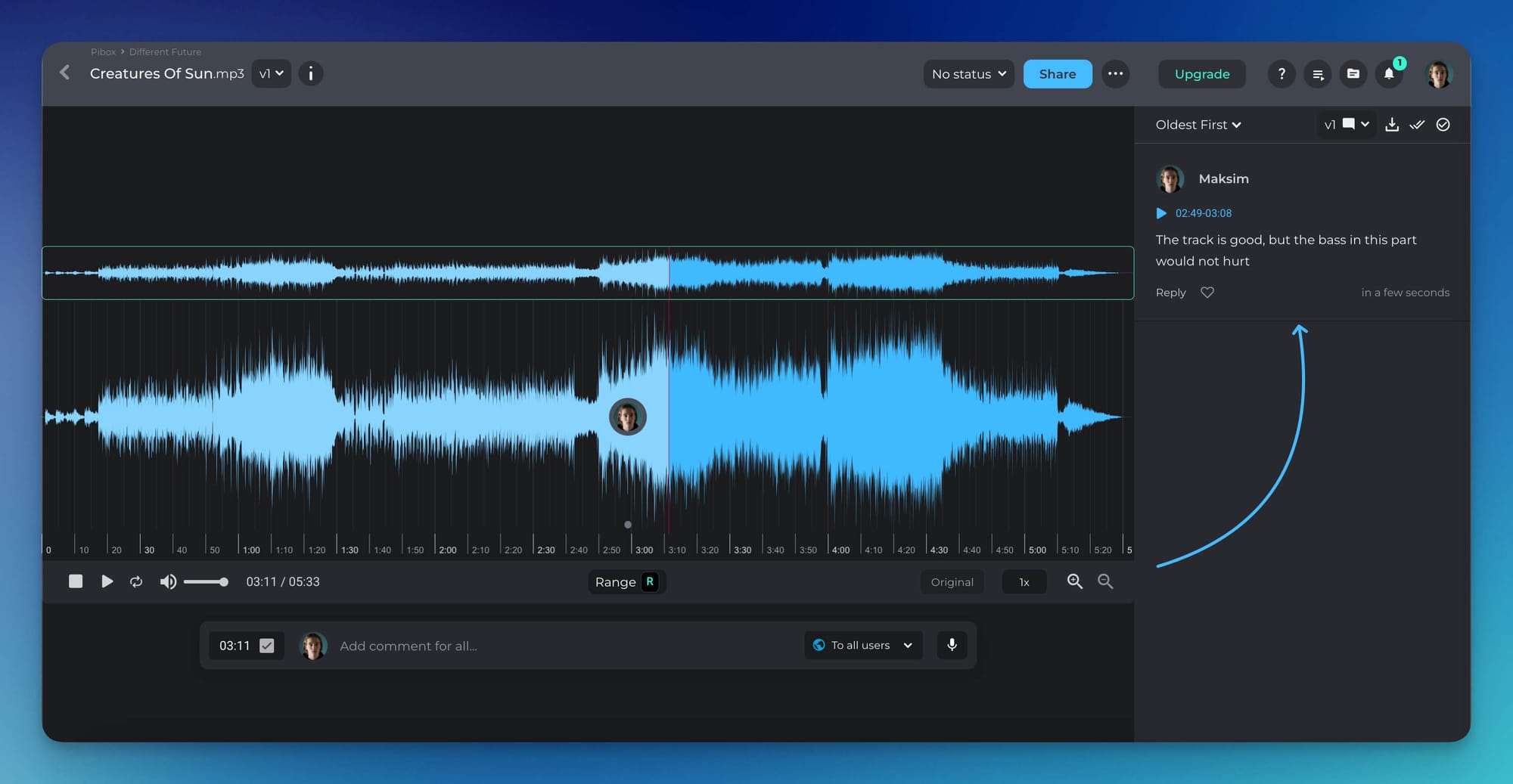

Platforms like Pibox allow him to map feedback to exact moments in the timeline, eliminating guesswork and saving hours.

What makes collaboration across disciplines actually work?

Whether working with directors, editors, or sound designers, Ray builds bridges between creative vocabularies.

“Directors speak in metaphor. It’s my job to translate that into music. And back again, of course. Successful collaboration is built on alignment of intent, not constant agreement.”

He shares frequency territory with sound designers carefully, avoiding midrange clashes. With editors, he delivers stems built for flexibility: stretchable, loopable, emotionally intact.

What’s the hardest part about remote composition, and how do you stay aligned?

Without the subtle feedback loops of in-person collaboration (body language, tone, silence), it’s easy to veer off course.

“The absence of ambient feedback is the most significant challenge. To mitigate this, I front-load the project with clarity. If there’s misalignment, I want to detect it in the opening days, not at final delivery.”

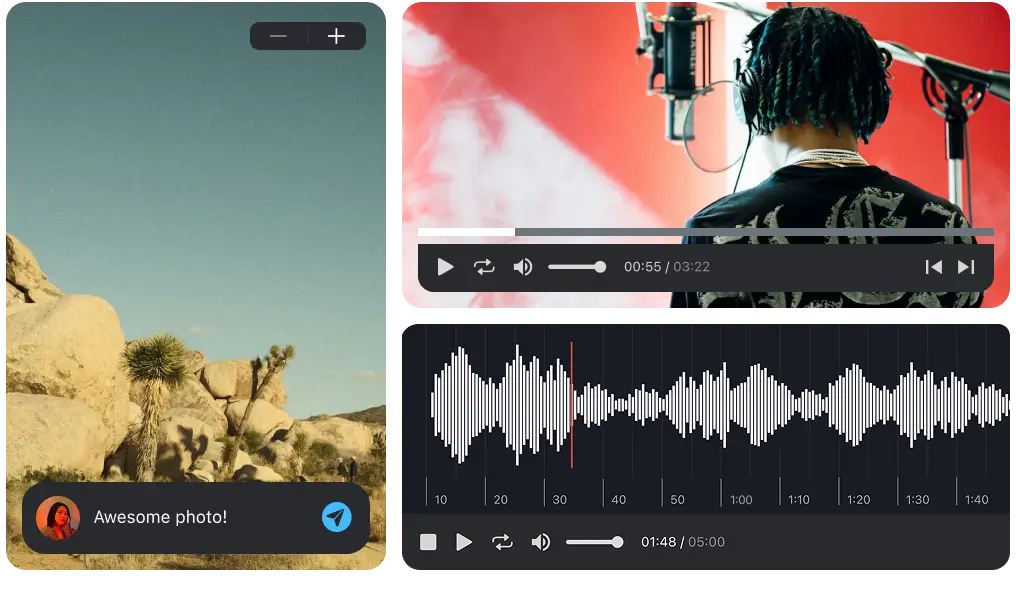

Pibox helps simulate studio-level precision, anchoring feedback directly to audio. It lets users leave timestamped text and voice comments directly on the waveform, bringing studio-level precision to remote collaboration.

How does Pibox actually support the creative process?

By embedding feedback in exact moments, Pibox eliminates vague, time-wasting revisions and preserves creative attention.

“A composer’s attention is a finite resource. Anything that protects that from fragmentation is more than convenience—it’s structural support. It’s not about replacing creative dialogue. Pibox enables it. What it offers is not automation, but clarity. In this work, clarity is everything.”

Especially on large or remote teams, Pibox ensures every change, decision, and version is trackable and explainable.

Pibox is the easier, faster way to collaborate in real-time, collect feedback, manage reviews, share, and finish your projects effortlessly.

How do I keep growing when I’m between projects?

Ray writes music no one will hear just to refine his instincts. He bans himself from plugins, writes in styles he dislikes, and copies tracks 1:1 to learn from them.

“Comfort is not an indicator of progress. Discomfort is where the next breakthrough lives. Growth is a function of confrontation. I love writing when no one is watching.”

By practicing without pressure, he isolates his habits and develops sharper creative reflexes.

How do you deal with conflicting feedback?

When stakeholders disagree—one calls a cue “too intense,” another says “lifeless”—Ray identifies the deeper tension.

“I respond with contrast. Two radically different versions let the real preference surface. A composer must function as an emotional interpreter, not merely a technician.”

If needed, he steps in to mediate emotional clarity across the team. It’s not about appeasement, but integrity.

Final Thought: What kind of composer do you want to be?

Edward Ray’s perspective challenges the composer to be more than a technician, more than someone who “makes things sound good.” His approach asks you to become a narrative listener, a workflow architect, and an emotional interpreter.

“Most of what I’ve learned came from asking: ‘What if I did less?’ Usually, it’s better.”

Let that question guide you.

Easier, faster way to collaborate in real-time, collect feedback, manage reviews, share, and finish your projects effortlessly.